This is a slightly extended version of a talk I presented at the Digital Library Federation 2018 Forum, held in Las Vegas in October 2018. Thanks to students in my Fall 2017 “Digital Public Humanities” course; the Providence Public Library Special Collections department; Diane O’Donoghue; Julieanne Fontana, Angela Feng, and Jasmine Chu; Monica Muñoz Martinez; Susan Smulyan; and the Rhode Tour project team for their contributions to my thinking and work on this topic. And thanks to Bethany Nowviskie for making DLF Forum a supportive space to consider these and other issues

So, “hyperlocal histories.”

What’s the difference between terms like local, regional, hyperlocal? I’m more here to tell you how I came to be invested in the term “hyperlocal” and less interested in having it overshadow or undercut other terms you’ve found useful in your own work. In the same way that recent pressure has been productively placed on our uses of the term “community,” on where, how, and why ideas of community are constructed, situated, limited by particular acts of language, my intention in introducing the “hyperlocal” as a framework is to see it in conversation with other words, use-cases, methodologies, implications.

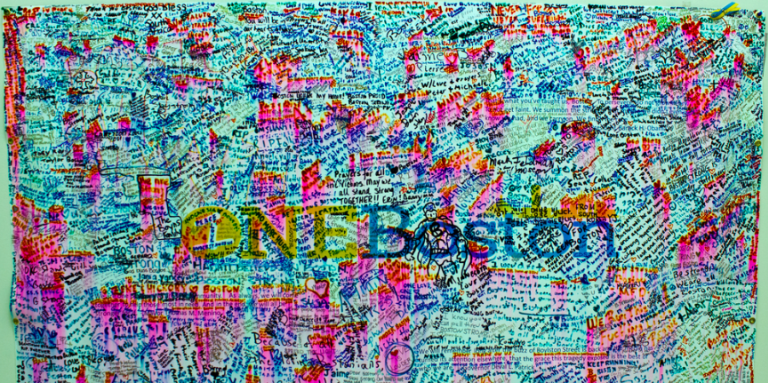

My professional interest in the hyperlocal began as a doctoral candidate at Northeastern University, through my work as Project Co-Director (with Alicia Peaker) of Our Marathon: The Boston Bombing Digital Archive, a collection of crowdsourced stories, photos, and memories of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings and their aftermath. Our mantra, reprinted on bookmarks and promotional content, was “No Story Too Small.” We were interested in created an accessible record of the bombings documenting a wide range of stories and perspectives.A project like Our Marathon is perhaps legible, familiar, conventional in terms of an approach librarians, archivists, faculty members, and community partners might take to work related to local and hyperlocal history. But it is also time and resource-consuming work, an attempt to address several perceived needs simultaneously: collecting, documenting, crowdsourcing, digitizing, curating, publishing, and preserving recent and still-unfolding history. There are other ways to do what we did, and certainly other ways one might get involved in work related to hyperlocal history.

Narratives of community formation and solidification, of competing claims and tensions, of fact and fiction and everything in between and beyond this binary, all of it can and should coexist in our records of hyperlocal history. These varied perspectives are frequently entwined and made further complicated by a city’s unwillingness to be one thing and stay that way forever, or even for a little while.

To work towards the goal of a crowdsourced, polyvocal, varied archive, we left Northeastern University campus, reached out to local libraries who had expressed interest in supporting our project, and planned programming that enabled us to introduce the archive and solicit contributions to a range of communities and neighborhoods. We used the content management system Omeka to encourage crowdsourced submissions and quickly make our collections materials public on the web.