Research into the visualisation of large cultural heritage collections has emphasised that search is only one way of representing a collection.

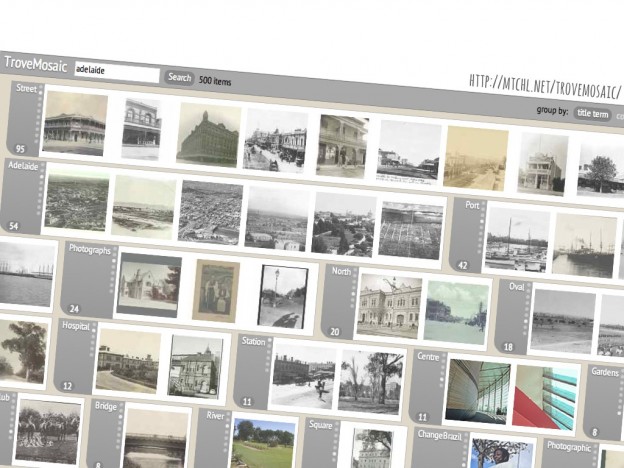

By focusing on the stylish minimalism of the search box, we discard opportunities for traversing relationships, for fostering serendipity, for seeing the big picture.

By creating experimental interfaces, by playing around with our expectations, we can start to think differently — to develop new metaphors for our online experience that are not framed around technological conquest.

My own Eyes on the past, which allows you to find your way into Trove’s digitised newspapers through machine recognised faces and eyes, is far from a practical discovery tool. But building on my earlier work using facial detection technology as a means of archival intervention, it opens up questions about the lives embedded within our collections — we see them differently, we feel differently.

A Google-like search experience offers utility at the expense of critique. Its technologies are black boxed, its assumptions obscured.

How can those of us in the discovery business create a buffer for critical reflection while still meeting user expectations? What can we do in a service such as Trove that supports many thousands of enquiries a day?

I’d suggest we start with an acknowledgement of our limits, an attempt to trace the edges and the fractures that are too often glossed over in our pursuit of seamlessness. Let’s start by admitting what Trove is not:

- Trove is not perfect

- Trove is not everything

- Trove is not a machine