In an early scene from Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, a casting agent warns the former star of a hit TV western against the kind of cameo roles he’s been taking since his show was canceled. Short a more permanent gig, the aging actor has been making guest appearances as one-episode villains on a number of newer action slots. The casting agent’s advice is something to this effect: you might think these roles are a good part-time gig, but every time the audience sees you beat at the end of the episode, they see TV’s up-and-coming action star besting the reigning champ. They’re using your decline to prop up some new guy’s rise to success. The real drama here is not between any particular episode’s hero and its villain, but between two dueling star texts.

Richard Dyer’s 1979 Stars introduces the concept of a star image or star text as the aggregate of every public appearance of, or reference to a given Hollywood studio actor. In Dyer’s terms, the star image is produced by the studio as a collection of mass cultural objects across a wide range of media. These would include the actor’s film and television roles, but also interviews, radio appearances, commercials, as well as published gossip, tabloids, and reviews. Part of what is most enabling about Dyer’s formulation is that it allows us to separate the celebrity as a real person from the public discourse around them. “Star text” is a term that helps us think about “stars” as “texts”—and not just texts, but narratives.

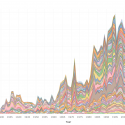

The Literary Lab’s Star Texts project departs from more traditional work on celebrity in both methodology and scale. Our project uses computational methods to trace large historical trends across a corpus of star texts, pursuing lines of questioning like: do star texts have genres? and, do they follow narrative conventions? Working through these larger conceptual questions, I wanted to test if we could already see these kinds of patterns emerging in a sample corpus. Stanford has access to the entire archive of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue Magazine,[1] let’s start there.